Reducing Deaths from Air Pollution

Exploreabout Reducing Deaths from Air Pollution

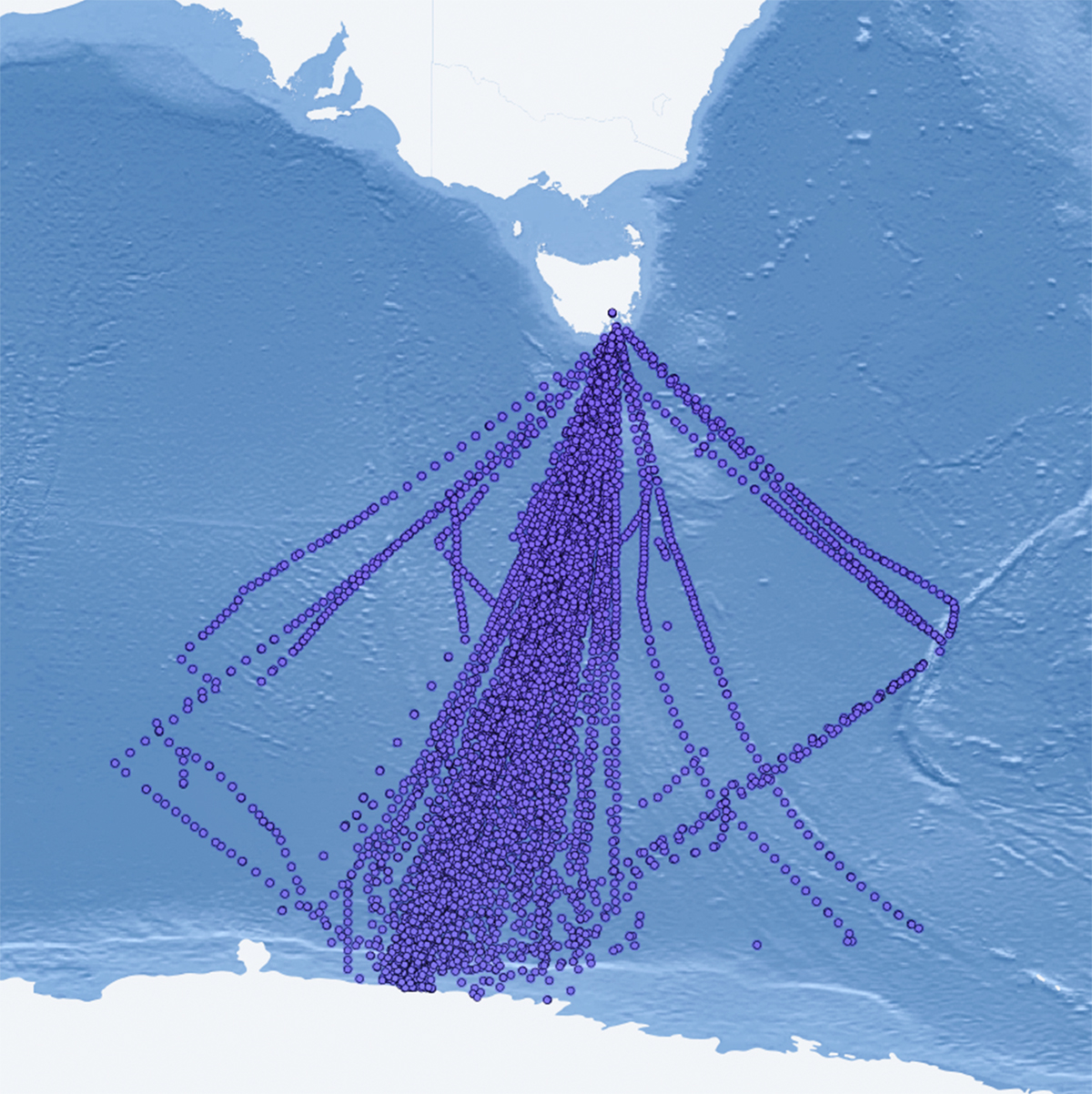

In 2021, an analysis of sea temperature data collected from the Southern Ocean over 25 years revealed disturbing evidence that the potential for Antarctic ice-sheet melting has been hugely underestimated in past studies. The resulting sea level rise could have dramatic impacts around the world.[1]

The unique time series of data was collected on board the French Antarctic resupply vessel L’Astrolabe, from 1992 to 2017, between Hobart and Antarctica.

It’s not unusual for scientific institutions to use volunteer merchant vessels to routinely gather observations. Known as ‘ships of opportunity’, they are a cost-effective way of collecting multidisciplinary oceanographic data for measuring the speed of change in the marine environment.

CSIRO data analyst and scientific programmer Ms Rebecca Cowley manages the Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) Ships of Opportunity program and is responsible for quality control and for sharing the data with other institutions.

CSIRO is part of the consortium that operates IMOS, which is enabled by the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

To record the ocean temperature, IMOS uses expendable temperature probes, which are deployed overboard at regular intervals. Attached to a long copper wire, the probe can sink to about 900 metres, and sends temperature data up the wire at various depth intervals, to an on-board system.

Within minutes, Ms Cowley can review the data from her office in Hobart and share it with the Global Telecommunication System (GTS), a global network for the transmission of meteorological data.

Within hours, the data is available to weather bureaus around the world, for use in climate modelling and forecasting, and is automatically added to Australia’s marine and climate science portal, the open access Australian Ocean Data Network (AODN). All this, with minimal human intervention.

A crucial part of what makes this machine-to-machine data sharing possible, streamlined and fast is the agreed research terminology, defined in ‘research vocabularies’, which institutions share and adhere to for describing collections of data – both the metadata and the data itself.

A vocabulary can be used to annotate data unambiguously; for example, the data must be attributed to the correct ship, so the name of the ship or its unique ‘call sign’ must already be registered in the AODN Platform Vocabulary or the data transfer will fail.

A research vocabulary can be as simple as a glossary or a list of codes that anyone in the research community can add to. Others, such as units of measure, taxa and rock types, are tightly controlled. The minimum requirements for a useful vocabulary are a unique label and a description or definition for each term in the list, though increasingly they also contain synonyms, intra-vocabulary relationships and cross-vocabulary mappings.

From plant taxonomy to disease classification, science depends on precise language and referencing. Finding evidence-based solutions to the grand societal challenges of this century requires that scientists use shared scientific concepts to pool their work. This enables them to aggregate vast amounts of data from multiple sources, often from multiple disciplines and domains, and from countries where differing languages are spoken. Clearly, unless a data collection is tagged using globally agreed terms, it cannot be part of the global web of information systems necessary for tackling challenges such as climate change.

Like research data, research vocabularies are best when they are FAIR – findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.

The ARDC provides an open, web-based service for publishing and accessing vocabularies. ARDC Research Vocabularies Australia is designed for people who support, describe and discover research – such as vocabulary managers, ontologists, data managers and librarians – and for researchers. It helps them create, maintain, find, access and reuse research vocabularies.

Several institutions host their vocabularies directly on ARDC infrastructure. Others are linked to on their home websites.

As of this year, 484 research vocabularies are openly shared on Research Vocabularies Australia by 87 registered publishers, including IMOS, TERN, Geoscience Australia and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. More than 100 people from research institutions are registered vocabulary contributors.

Some of the most heavily accessed vocabularies are a ‘fields of research’ vocabulary, a public policy taxonomy, an astronomy thesaurus, and an index of psychological terms.

158 of these vocabularies come with a readymade tool, or ‘widget’, which users can ‘plug in’ to their own data capture tools, allowing them to draw directly from ARDC-hosted vocabularies to classify their data.

An independent evaluation by CSIRO of Research Vocabularies Australia in 2019 found that it “is meeting a clear need, and provides a suite of capabilities that are valued by the community.”

A vocabulary is not only useful for humans, but also for machines. ARDC-hosted vocabularies follow contemporary best practice whereby each term is allocated a unique web identifier.

The information is structured using the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), the W3C recommendation for representing vocabularies in a format understandable by computers. This supports interoperability and reuse of the vocabulary term, and discovery and integration of data.

Dr Natalia Atkins is the metadata manager for all IMOS vocabularies used in managing the Australian Ocean Data Network. She creates all the metadata records for IMOS content, using vocabulary terms such as the vessel name and the name of the organisation that collected the data.

“We created our vocabularies to make the IMOS data collections more discoverable. We have separate vocabularies which are used for different workflows. The main use of our vocabularies is for driving the faceted searching on the AODN portal,” said Dr Atkins.

The vocabularies are also used in the data ingestion process [to AODN] to ensure that it is catalogued in a systematic way. “Water temperature is a good example,” said Dr Atkins. “Some people call it ‘temperature of the water body’, others call it ‘sea temperature’; then there’s ‘sea surface temperature’ or ‘SST’. If you don’t mark things up in a systematic way, you can never be sure it’s the same [thing].

“We also try to have good governance and part of that is not reusing terms already used in other vocabularies.”

For example, if a term already exists in a vocabulary of the British Oceanographic Data Centre – whose vocabulary service is the point of truth for many international oceanography initiatives – Dr Atkins will link to it from the IMOS vocabulary. Not only does this avoid duplication, it ensures the definition is always up to date, and the provenance of the definition is visible for all to assess.

Through the power of the semantic web, vocabularies are evolving beyond the simple concept of a dictionary or thesaurus and are beginning to be shared across disciplines and domains.

It’s important that the research community signs up to use vocabularies in their metadata and data. The ARDC plays a leading role in promoting FAIR research vocabularies in Australia and internationally, not just through our Research Vocabularies Australia service but also through our support for the Australian Vocabulary Special Interest Group and through facilitating several working groups.

As the faraway, menacing drip of melting ice grows ever more insistent, dissolving the barriers that prevent researchers from sharing data quickly and easily has never been more necessary.

Written by Mary O’Callaghan. Reviewed by Jo Savill, Rowan Brownlee, Dr Lesley Wyborn, Rebecca Cowley, Dr Natalia Atkins, Dr Marian Wiltshire, Dr Adrian Burton, Natasha Simons, Adelle Coote, Ian Duncan, Rosie Hicks